THE HARDWIRING PROBLEM

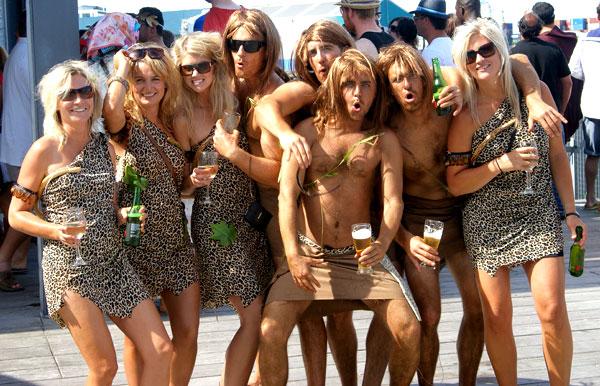

When it comes to investing, we’re still all cavemen (and cavewomen).

There is no doubt that rationality is overrated and that behavioral elements in our daily lives are far more important than we all care to admit. Nowhere is this more evident than in investing, where research has shown we are at our most vulnerable. My friend Dr. Steven Bates, CEO of QLAB Invest Ltd, has done a superb job of outlining the uncomfortable reality in this brief paper, as well as suggesting a course of action. I cannot do justice to Steven’s work in 500 words or less, so take 10 minutes and read it.

In my interpretation, behavioral issues are not merely the outcome of complex interactions among individuals or of the increased rapidity with which our modern society operates. It is a matter of hardwiring: our internal physical make-up or neuronal interconnectedness has not evolved as much as our surroundings; it’s stuck at the stone age. This is another way of saying we are born bad investors, though as always there are exceptions to the rule.

Our physical shortcomings do not imply we are doomed to utter haplessness in managing money. Once we recognize the problem and we make a little effort to know ourselves, things have a chance to improve: we can look for solutions. Our compulsion to seek immediate satisfaction and consequently treat every investment as if it were a piece of paper needs to be dominated, not simply controlled: investments should be viewed in terms of the underlying cash flows. Also, our fascination with cleverly thought-out investment schemes and aptly marketed trading ideas must be scrupulously dealt with: today, with reams of historical data at hand, we can ask how an investment process works and to what extent its results are replicable in the future.

Steven speaks of “systematic investment processes” as a viable alternative for at least a portion of one’s investable wealth. These processes have the advantage of being several steps removed from the emotional vagaries of our brain in the midst of an investment decision. They can also be analyzed and dissected more scientifically than non-systematic (or sit-at-your-desk-and-decide) processes since their formulaic approach makes them fully transparent and accessible. The disadvantage (in my experience, but not necessarily in Steven’s) is that they tend to work well in most market environments but possibly not all of them. I’m not exactly sure why this is, but I suspect it has to do with the implicit trade-off we bargain for when we opt for “insensitive” mechanical solutions: while flawed, human behavioral qualities and survival instincts may be invaluable in some cases.

A parting word of caution. Just as we should never underestimate the power of our behavioral limitations, we should also not take our eyes off the pervasiveness of randomness in the real world. There are not enough words to describe how important this is. For an entertaining and informative read on the subject you should get a copy of “Fooled by Randomness”, by Nassim Taleb; a good and riskless investment, if there ever was one.

Photo sources: http-//www.costumepedia.com/homemade-cave-people-costume-ideas/2.