In Pursuit of Dreams

High cuisine, painting, composing and investing: not all crafts are treated equally.

Yesterday I watched the episode on Grant Ashatz and his restaurant Alinea in the series Chef’s Table (Netflix), and I learned how two years after the opening Ashatz found out he had cancer of the mouth.

Understandably people might hesitate eating at a restaurant with a chef without taste buds, or buying a painting from a blind artist, or listening to music by a deaf composer (though we are aware of examples like Ashatz, who fully recovered, or Monet and Beethoven in their later years). Less reasonably this logic does not apply to investing, where we don’t observe the same level of prudent behavior: humans are clueless about the future and forecasting, yet many investors (individual and institutional) are still ready to give money to the next active manager. As I was explaining to a prospective client, the story behind this anomaly evolves more or less as follows.

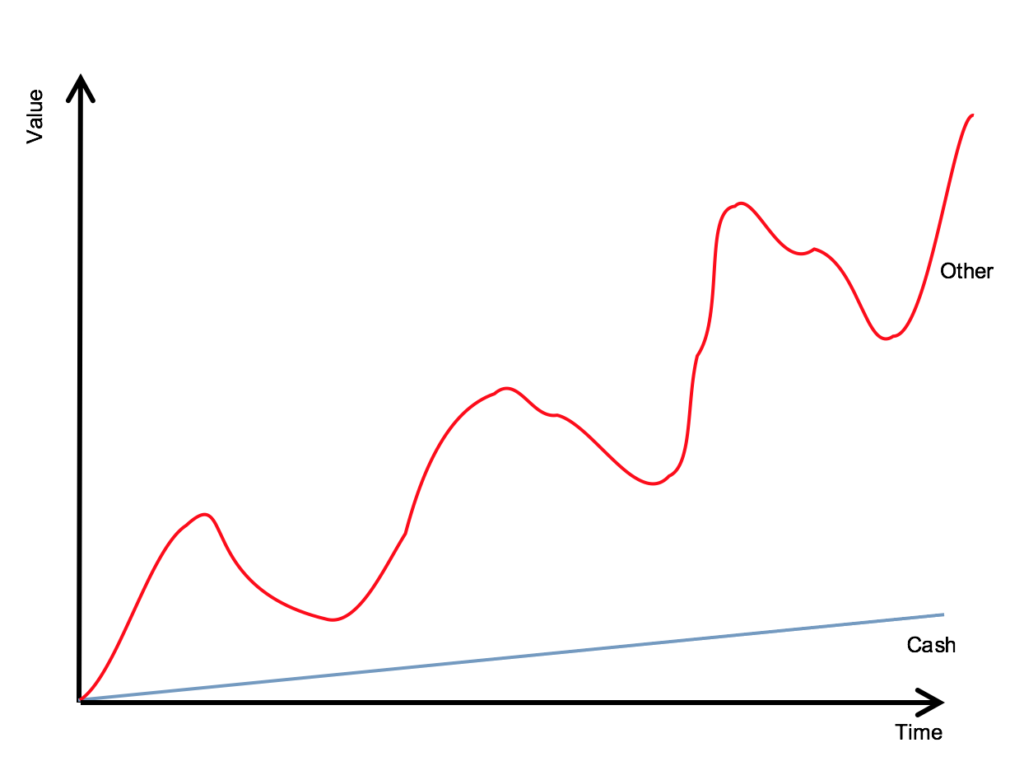

We know the real behavior of assets across time approximates the lines in this picture (I never learned how to draw so please bear with me):

Figure 1

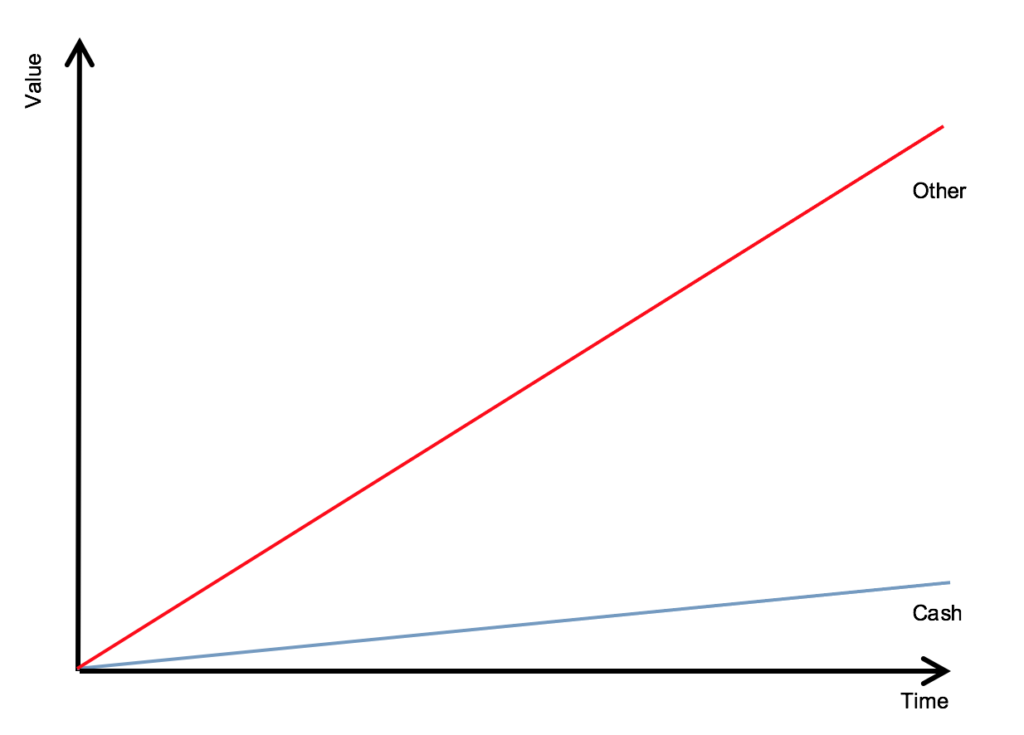

However, we wish (and sometimes subconsciously believe) the same assets behaved more like in this picture:

Figure 2

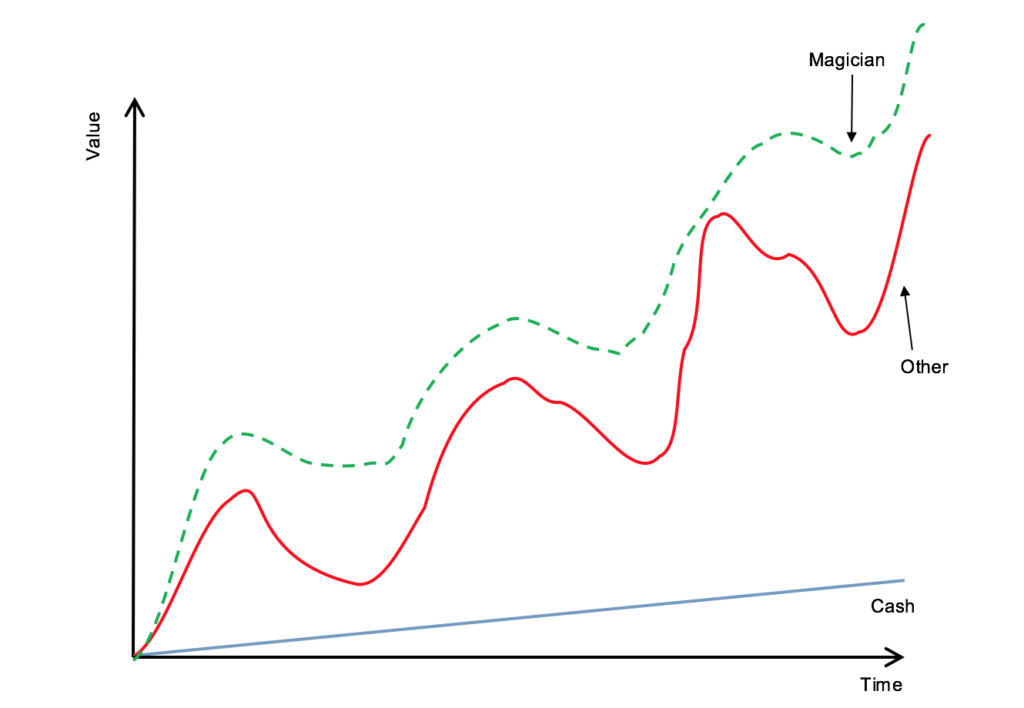

In the indefatigable search for the desirable pattern we look for the magician (portfolio manager) who will lead us to a gentler superior path:

Figure 3

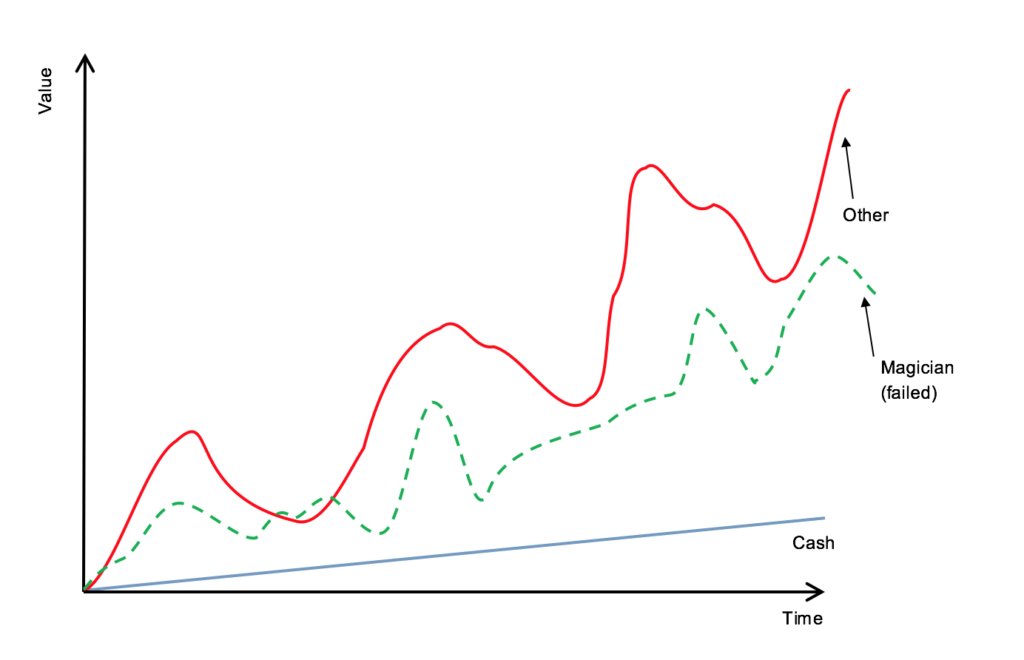

Often, though, we end up with disappointment and frustration:

Figure 4

Obtaining results similar to the ones stylized in Figure 3 requires a level of clairvoyance which is out of reach for all managers except maybe a handful. After all it costs $500 per person and a wait of several months for a seat at Alinea, and you have to shell out tens of millions for a late Monet, if you can find one. Despite this evidence, most investors keep going back for more of the same by changing positions, allocations, funds, bankers, sectors, size, leverage, region and what not just to keep after the dream.

Why not settling for just capturing the natural evolution of the markets, perhaps with a shift or two in a cycle to adjust for value dislocations? Part of the answer is the desire to “win”, one that is as hard to control as it is futile. In a recent post in Italian I pointed out that the definition of winning is often more a perverse case of keeping-up-with-the-Joneses than a well thought out objective. The other consideration is that “capturing the natural evolution of the markets” appears deceptively static or boring, not as sexy as trading day in and day out (what I sometimes refer to as the watching-the-grass-grow syndrome). Whatever the motivations, on top of all this we have a naturally evolved, regulated, competitive and well organized industry that is willing to help us dream ad infinitum; the kind of stuff that if it involved the distribution of physical substances we would call legalized drug dealing.

Think of investing as of any other serious and appreciated craft: start with the logical and never stop looking for the exceptional.

-Photo Sources-

Cover: https://seafoammedia.com/4-life-hacks-to-be-more-productive-at-work/

All graphs were made by the author on PowerPoint.