Know Where You Stand

It’s very important to know where you stand, particularly in terms of your investments. Most people don’t consider the issue nearly as seriously as they should and because of that they end up in real trouble.

Take the case of investment returns. I am often asked to comment on a portfolio’s performance, usually after the investor volunteers views on the matter: “He’s done very well in the last few years,” or “I got my 6-7%; it’s fine,” or other variations on the theme.

Relative (he’s done very well…) or absolute (…my 6-7%…) statements like the ones above are not helpful nor indicative of skill. To say that someone has done well or that your portfolio returns are fine requires some organizational work. Just as in the world of art (where to appreciate the aesthetic value of a superb painting you must have been exposed to some awful stuff), investment returns need to be put in context. At a minimum we need to relate them to the chosen asset allocation and to the opportunity set available in the markets.

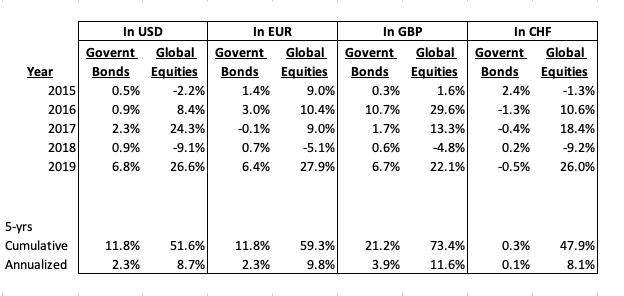

The asset allocation is necessary because it sets the risk level of the portfolio. Using two ETFs per currency, one for global unhedged equities and one for local currency government bonds, here is what returns were like in the last five years:

Figure 1

You can easily use this table for comparison purposes, even for different asset mixes (e.g., a USD 50% bonds/50% stocks portfolio would have returned 5.5% in the five-year period or 16.7% in 2019).

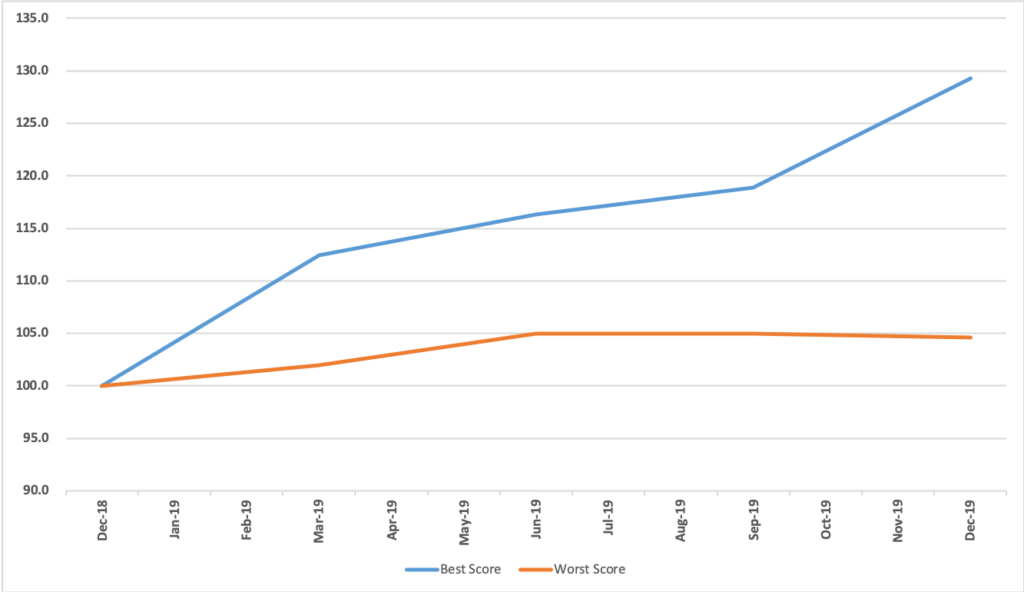

To broadly estimate the opportunity set in any one year, we can define hypothetical boundaries by calculating the returns obtained if we invested in the best asset class every quarter (upper bound) or in the worse one (lower bound). For 2019, using the same two ETFs in USD, the results look like this:

Figure 2

If you were a genius you would have gained almost 30% (pretty close to simply owning equities all along); if you were an idiot, you still took home 5%. In other words, 2019 was a year in which it was tough to lose money.

These simple tools will go a long way towards confirming whether an advisor has done well for you or not in a given period and will also help you in determining an achievable rate of return.

A final note of caution. I often hear that if the returns are ‘good’ (see above) an investor should not worry about how much it costs to obtain them. This concept is what convinces people to leave 20-30% of their gross investment returns to private equity or hedge fund managers (even the good ones). This is wrong because the investor gets the net returns (good or bad) while incurring the totality of the risk. You may choose to pay what you wish; just make sure you are cognizant of the math.

Roberto Plaja, 28 February 2020

-Cover- ‘Angel of the North,’ by Anthony Gormley, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Angel-of-the-North